A Wedding Story

How a single encounter changed someone's life--featuring Yasser Arafat, the Harry Potter producer, and me dancing the Dabke.

This is a longish post involving the West Bank, Vancouver, Montreal, Thunder Bay and Kentucky, in which Yasser Arafat and the producer of the Harry Potter films make cameo appearances.

The story also involves a three day wedding during which I never clap eyes on the bride, but I do repeatedly dance the Dabke. Obviously I understand that many of you will be here only to see me dance the Dabke. So let’s get that out of the way and you can get on with your life.

OK, we’ve thinned out the crowd. If you have decided to stay simply to mock me, believe me nothing you can do will match the derision I suffered at the hands of the young Palestinian men who were there. If you have stayed for more kindly reasons, I promise you, gentle reader, there is more to this story.

The setting is the village of Al Yamoun, a few kilometres outside of the Palestinian city of Jenin in the West Bank. It is the summer of 2019, and I am there to celebrate the wedding of my friend Abdalnaser to his beautiful bride Samah. It is my second visit to the village. The previous was in the summer of 2003 and I can say without reservation that the earlier visit changed Abdalnaser’s life.

But before I get to that, I want to introduce you to another character in this story. This is a picture of me with my friend Nuha in that same summer of 2019, visiting Herodian ruins in Jericho. Nuha is a woman of extraordinary and various talents. To give you an idea, when I was the Globe and Mail’s Middle East reporter in the early 2000s, Nuha had a business card that stated underneath her name: “language lessons, antiquities, journalism”.

Nowadays, Nuha has a beautiful shop in central Ramallah where she and her husband sell antiques and contemporary-but-traditional Palestinian textiles and jewellery. When I was in the region with the Globe, she was my “fixer” in journalistic terminology. That means she was my translator, but also a sort of producer and researcher: figuring out how to sneak by Israeli patrols and how to track down Palestinian officials or militants from Hamas to interview. I could write a whole post just about Nuha and maybe someday I will, and it would say a lot about her stunning physical courage and absolute ferocity in pursuit of a story. But if I do that all now, I won’t ever get to this story, and I imagine you may be getting impatient.

So. It was mid-summer 2003 and Nuha and I were travelling somewhere in a Palestinian communal taxi, which people called trans-eets because they were usually Ford Transit vans. In that part of the world, at that particular time—the so-called Second Intifada—everyone, Israeli or Arab, listened to the news all the time and the news was on in the trans-eet. Suddenly, Nuha shrieked. (This is not a figure of speech; Nuha is not a quiet person.)

What had so excited Nuha was an item on the news about a boy from a village near Jenin who had just got the highest grades in the Palestinian territories on the final high school exams, roughly the equivalent of the British A-levels. The reason this was extraordinary was that the area around Jenin had been one of the centres of the violent clashes then underway between the Israelis and Palestinians. Jenin had become famous, even internationally, for all the suicide bombers it produced. And not surprisingly that meant that it was the also the site of incessant Israeli raids.

Nuha’s shriek was at the thought that a boy living in those conditions could find the quiet and the composure to excel academically. That boy was Abdalnaser Zayid.

Nuha wanted to do a story right away. For my part, I was about to go on vacation back to Canada and I did not share her sense of urgency. Partially to placate her, I suggested that a better time would be when I came back from my holidays because I could pitch it to Toronto at the end of the summer as a back-to-school story. This was mid-July and nobody wants to read about school in July, I said.

While I was gone, something interesting happened. Yasser Arafat—at the time not only the leader of his party, Fatah, and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), but now also President of the Palestinian National Authority under the Oslo Accords—was a man given to extravagant gestures. Arafat had arranged to meet Abdalnaser to celebrate his accomplishment, proclaiming that he could go anywhere in the world he wanted to pursue his education, on the Palestinian Authority’s dime—a promise that had been heralded on the pages of the Palestinian newspapers.

When I returned from my vacation, I suggested to Nuha that we pursue the story. This was not an easy process. At the time, phone service in the West Bank was spotty and Palestinians who had cell phones tended to top them up only when they happened to have some cash or a particular need to make a call. It took Nuha a few days to track the family down and we set off from Jerusalem in a yellow cab, driven not coincidentally by Nuha’s brother Yusef, whose many talents included an encyclopedic knowledge of the West Bank’s back roads and Hebrew so impeccable that he could pass as a Jewish Israeli, a valuable skill at military checkpoints.

Because of the communication problems, we didn’t know exactly what to expect. When we approached the family house—the same one I am dancing in front of in the clip above—we saw that it was damaged. As we were later told, the tiny grocery shop on the main floor lit by a single bare bulb and run by Abdalnaser’s mother, Fatima, had been scarred by Israeli gunfire.

The story I had imagined I would find in Al Yamoun was perhaps that of young man packing as he set out for a university in Europe or North America. Instead, we met a dejected, slightly overweight 18-year-old boy who to my eye seemed like he might be clinically depressed. In a voice so soft it was difficult to make out, he spoke movingly of his accomplishment. "There were tanks in front of the school," he told us. "The soldiers were raiding the houses. They arrested boys from my own class during exams. It disrupted my schooling, but I had to concentrate on what was important to me."

The reason that he was downcast was that instead of packing for school, he was going nowhere that autumn. Arafat’s seeming generosity had all been a sham.

Here is what I wrote in the article that was eventually published in the Globe and Mail at the end of August:

Meeting with Mr. Arafat was a highlight for Mr. Zayid, if only because from then on, his academic prospects have been rolling downhill. Mr. Zayid, the youngest of 12 children, wants to follow in the footsteps of one of his older brothers, Muhanad, who has just graduated from a university in Germany, where he studied medicine.

"I grew up to hear this every day: Study and you'll be a doctor," Mr. Zayid said. "A doctor has a respectable position in society. He gets the praise of God and his neighbours."

When Palestinian officials contacted him to make good on Mr. Arafat's promise, however, Mr. Zayid said they told him he would not be sent to Germany. Rather he would have to choose from a list of countries including Turkey, Greece, Jordan and Morocco.

Later, he was told the options had narrowed again. It was the University of Jordan or nothing.

Then, astonishingly, he received a phone call telling him he would have to enter a lottery with two top students from the Gaza Strip for the available places at the University of Jordan. He lost.

The consolation prize was an offer to study at the military college at Muata, in rural Jordan.

"I was shocked," he said. "It was hard enough to accept that I might be going to the University of Jordan. Now, here I am at the very bottom."

The Globe and Mail gave the story prominent play, under the headline Arafat offers moon, delivers military college.

Something none of us could have expected was the reaction to the story’s publication. It was early-ish days in terms of news on the internet and the way links got circulated by email. Within a few days, I received many offers of help. A group of people on Bay Street contacted me: they thought they might try to raise money to bring Abdalnaser to the University of Toronto. A man who said he was a millionaire in Malaysia wrote to say he was willing to provide for Abdalnaser’s education there. I passed these offers along to him via Nuha, who was still negotiating the difficulties of communication. He also got an offer to study at UBC in Vancouver.

Much later, at the wedding, I met Moh Faris, a retired Lebanese-Canadian businessman and philanthropist who had taken an interest in Abdalnaser from the start. He told me that at first Abdalnaser had vacillated between going to Germany to study and coming to UBC. Moh said he got on the phone with Abdalnaser’s father and convinced him that they would take better care of him in Vancouver.

I didn’t fully realize until many years later that while I had little further involvement with Abdelnaser at the time, Nuha was all in. With the ubiquitous Israeli military checkpoints in that era, it wasn’t easy for Abdalnaser to get to the Canadian Representative Office in Ramallah to arrange his Canadian visa and she shuttled between there and Al Yamoun to ensure it all got straightened out. Don’t ever be on the wrong side of a bureaucratic desk with Nuha.

One day, while all this was happening out of my sight, I got a call on the cell phone at my home in Herzlia Pituach, north of Tel Aviv. A man introduced himself as David Heyman, a name that did not mean anything to me. However, he explained that he was the producer of the Harry Potter films. He had read my article sometime earlier but he had been busy working and travelling. He offered to pay for Abdelnaser’s entire education as long and as far as it would go. I explained that Abdalnaser was already looked after and stupidly I did not even bother to get Heyman’s contact information. If it had all fallen through for Abdalnaser at UBC, I might have lived to regret that.

But it did not fall through. His trip from Al Yamoun was harrowing enough. He not only had a heavy suitcase, but also a gallon of prized Palestinian olive oil being transported to a relative in Germany. (Those not familiar with Palestinians may find this peculiar, but many of them operate on the belief that the local olive oil is so special that the rest of the world lives in a perpetual state of deprivation.) At one point, Abdalnaser unexpectedly encountered a so-called “flying” Israeli checkpoint. Fearing they might not allow him through on his way to Jordan to catch his plane, he made a dash through the woods, suitcase and olive oil in tow.

In Vancouver, he was at first taken into the home of UBC’s international student coordinator, Karen McKellin, and her husband, Bill, a professor at the university. Although he had excelled in his English exam, like all his others, his verbal English skills were not strong when he arrived. UBC set up a special regime of English classes to give him the time needed in his first year to get up to speed. The Faris family invited him to dinners at their home where the language and the food was more familiar, and they along with the McKellins, provided the nucleus of a support network that helped get him through his degree in biochemistry.

"When you think about it, what if Paul Adams didn't contact me to do that story?" he marvelled. "I would still be on the West Bank for sure. Maybe carrying a gun. Who knows? That one call changed my life."

(From a story in the Globe and Mail by Rod Mickleburgh, May 24, 2008)

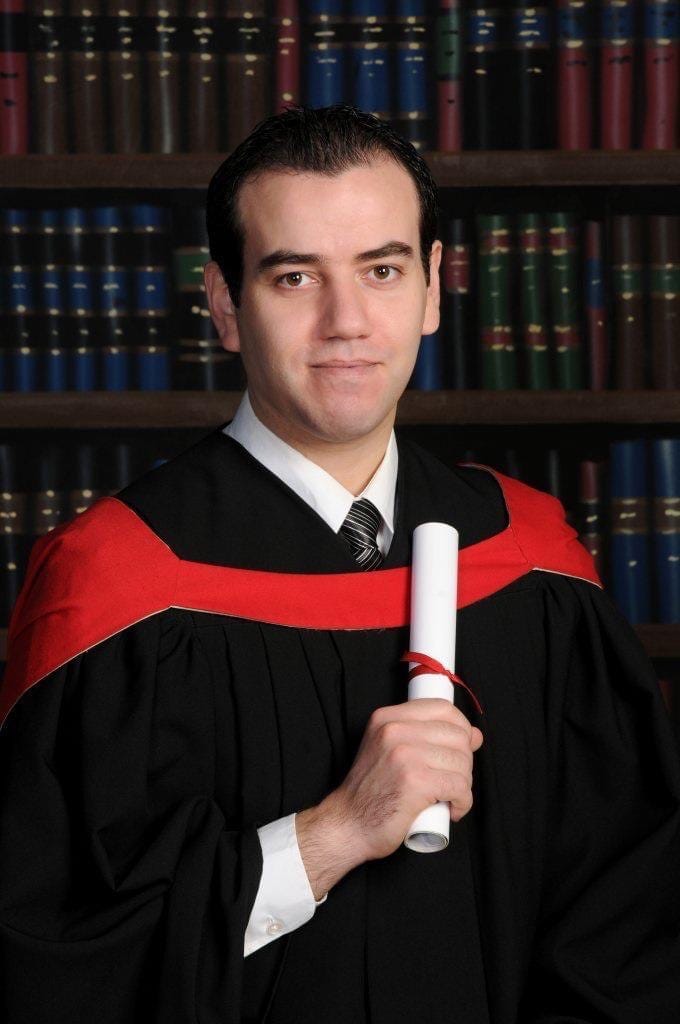

The next time I saw Abdalnaser was on a business trip to Vancouver. I had long since left the Globe, though my former colleague Rod Mickleburgh, in the Vancouver bureau, wrote a couple of stories charting his progress. Abdalnaser and his then-girlfriend had dinner with Karen McKellin and me. In place of the shy chubby boy who barely spoke English, was a handsome, trim, confident young man who spoke with not much more than a trace of an accent.

Not long afterwards, Abdalnaser graduated from UBC, and with the help of his now-substantial support network, he headed to McGill to study medicine. In 2013, he graduated there and moved to Thunder Bay of all places, for a residency in general surgery. In one of Rod’s articles, he recounted Abdalnaser’s shock when it snowed on his second day in Vancouver. But now he was acclimated enough that he loved the access to the frosty wilderness around Thunder Bay.

Over the years, Abdalnaser and I stayed in occasional contact. I was surprised in the winter of 2019, when I went to see my father in my hometown of Winnipeg, to discover that Abdalnaser was working in orthopaedic surgery there. We had a lunch together and I was touched by the deference and respect he showed to my father, formerly a physician, now in his late nineties. That’s when Abdalnaser told me he was getting married that summer in Al Yamoun to a young woman from the village.

A few months later and I was riding up from Jerusalem in a cab with a Arab-Israeli driver who was distinctly edgy about going so deep into the West Bank—though to tell the truth, it seemed less tense than I had remembered from the time of the Second Intifada. As we were driving though Nablus, I got a call saying that Abdalnaser and Samah were having lunch there with the other out-of-town visitors. I’m glad they reached me because, though I didn't know it at the time, that was the only occasion on which I would meet Samah. I was too late for lunch, but not too late for a stroll through the Nablus market.

That evening, the men gathered at the family home in Al Yamoun, and as I realized later was the pattern, there were hours of celebratory dancing, but strictly men-only. Sometimes you could see the little girls in the family peeking out of the upper floor windows to watch the spectacle. As the evening drew on, enormous meals would be served on tables in the still-warm Palestinian summer evening air.

Given their humble roots, the Zayid family has been amazingly successful. All twelve children are professionals—doctors like Abdalnaser, a dentist, a nurse, a building contractor, and so on. There is a tradition of lavish hospitality among Arabs in general, and Palestinians in particular. The small clutch of foreign guests, of which I was one, were especially warmly embraced—often literally.

I was housed during the three days of celebrations with a physician from Vancouver, Paul Theissen. The first morning we awoke to the sound of sharp bangs and pops. Paul said they must be setting off fireworks. I pointed out that no one sets off fireworks on a bright sunny summer morning. It was obviously gunfire, but I could not imagine what for. At breakfast we asked, of course. Appropriately enough, it turned out to be celebratory gunfire because the high school exam results had just been released—the same event that connected me with Abdalnaser 16 years earlier.

As it turned out, it was not to be our last encounter with celebratory gunfire—a distressingly widespread tradition in the Middle East. Abdalnaser’s family had made it clear that they did not want that tradition to be part of this wedding. But one evening an official from the Arafat’s ruling Fatah party showed up in a luxury SUV and pulled out an automatic weapon which he proceeded to shoot into the air. When a guest pulls out a machine gun, it behooves everyone to be polite, I guess. My roommate Paul got out his phone to take pictures. Perhaps I was being overly cautious but I suggested to him I wasn’t sure that was a good idea for us obviously non-Arab men to be snapping photos of a Fatah official with a gun.

It only slowly dawned on me that the wedding I was attending was, in effect, two weddings. One was hosted by the women of the village and featured the bride. The only man to take much part in those celebrations was Abdalnaser. He shuttled between that wedding and the men-only wedding I was attending.

On the afternoon of the second day, the women conducted their event in a large hall, while we men sat outside drinking tea and the younger children played around us.

Perhaps needless to say, virtually all of the women attending the wedding wore hijabs—one conspicuous exception being the Arab-Israeli wife of one of Abdelnaser’s brothers, herself a physician practicing in Germany. (She is in the middle of the second row in the photo immediately below). So it was striking that the young girls who hung around outside with the men were attired in party dresses.

On the climactic, third day of the wedding celebration, Nuha made her return to the story. She had driven up from Ramallah to join the party and pick me up on our way to Jericho. I was outside drinking tea with the men while the real action took place inside with Abdalnaser and the women. Somehow Nuha and I missed each other when she arrived and so by the time of our first encounter she had already been into the hall with the women.

Nuha grabbed my arm and said loudly, “You need to come inside. You can’t come all the way from Canada and not see the bride looking so beautiful!” I objected that the men were not allowed in, to which she shouted in reply, perplexingly, “You’re a journalist!”—as if this de-gendered me for the purposes of wedding etiquette.

At this point several of Abdelnaser’s brothers, who had been wonderfully hospitable to me throughout, jumped in and argued loudly with Nuha in Arabic. I was rooting for the brothers, not wanting to make a scene, or rather wanting this scene to end and not to become something life-changing for me, Nuha or the family. Eventually, one of the brothers defused the situation by saying that I would be allowed in later in the day when the family menfolk would be brought in briefly.

Sadly, that never happened. Or rather when the appointed time came, they didn’t find me.

Meanwhile, Nuha grabbed a plastic chair and sat outside gossiping and telling stories—the lone grown woman among the scores of men. Later, as the women shuttled into a neighbouring dining hall, Nuha stayed with us. Only when the women left and it was the men’s turn to eat did Nuha join the feast, laughing and trading stories in English and Arabic with the men. None of the men seemed bothered by her presence.

This may be entirely wrong, but it occurred to me that perhaps the shame of mixing sits solely with the woman, which is why it was so strongly forbidden for me to go in with the women, but not an issue for Nuha to sit with the men.

Eventually, a band started to play and the men began to dance again, this time in high style. As usual, this involved Abdalnaser, who told me he had been practicing, dancing on the shoulders of other men, often with his brothers, similarly perched.

At a certain point, as the band continued to play and the men continued to dance, Abdalnaser went up on the stage and a long line of men assembled. Each of us in turn would mount the stage, drop an envelope stuffed with cash into a basket and pose for a photo with Abdalnaser. As I queued, at one point I casually looked back to see how long the line of men was, and there, a dozen or so spots behind me, was Nuha, the lone woman, with an envelope in her hand.

With that ceremonial done, Nuha and I got ready to leave on our drive to Jericho. At this point she informed me that she did not like driving in the West Bank in the dark, so that I would be doing the honours.

On the way to the car, I made sure to seek out as many of the brothers as I could find to thank them for their lavish hospitality. As one of them who happens to live abroad embraced me, he apologized for restraining me from entering the female side of the wedding earlier in the day. “I don’t care about it,” he said, or perhaps something saltier to that effect. “But my family has to live here and it would bring shame to them in the village.”

And that, as they say, is that. Though someone did later send me a wedding day photo of the bride—or rather a photo of a photo—which I share with you here.

Postscript: The attentive reader may have noticed that there has not yet been the promised reference to Kentucky. After the wedding, Samah, who had not previously been outside of Palestine, moved to Springfield, Illinois with Abdalnaser, where he had a new surgical posting. They had their first child, a boy named Taym, early in the pandemic. Subsequently, they moved to Greenville, Kentucky, where Samah is happier, not least due to the climate. They now have a second boy, Ryan. My understanding is that they have not been able to return to Al Yamoun for a visit because of visa issues.

I hope to visit them sometime this year. I will keep you posted.

Attending the wedding was truly one of the most amazing cultural experiences of my life, and the hospitality the family extended was unbelievably warm and exuberant

You have a life of wonderful memories.