China

A brief travellers' guide

Shortly after arriving in Ningbo, China, we went to an excellent restaurant which like many of the best ones here is located in a brand spanking new mall. When nature called, I answered and went to the restroom. I was standing at a urinal when I heard a loud “HELLO!”

At first I didn’t realize that this was directed at me. Then, another loud “HELLO!”.

I turned—well only my head turned to be technical—and there I saw a man standing with his torso protruding from one of the cubicles, smiling broadly at me. “HELLO!” he said a third time.

I smiled back and replied “hello” (the lack of all-caps suggesting a restrained tone) which turned out to be exactly what was expected of me, thus ending the exchange with satisfied smiles all round.

Over the next few days, I had this happen several times, once in an elevator, once on the street. “HELLO!” said rather too loudly and then the expectant grin, preparing for my apparently amusing reply: “hello”. The exchanges seemed more curious than friendly I would say.

Then one day outside a Starbucks at the edge of Taizhou’s walled city, a high-school age girl who was with a group of friends said “HELLO” and after I replied in my way, she paused and in studied English asked, “Do you know any Chinese?” I said that I did not, and then she asked in careful but correct English, “Where are you from?”. When I said Canada, she exclaimed “Canada! That’s so cool!” She smiled in delight and then turned back to her friends, to discuss the encounter, I am guessing.

China is a fascinating place to visit and is no doubt much easier for a tourist than it once was. But it presents particular challenges, including culture, language, money, and technology, among others. There’s also the issue of getting a visa which some may be interested in, though I will leave that to the end of this post because it is pretty boring.

Language

In Shanghai, the clerks at our hotel, an Andaz, spoke reasonably good English as did waiters at the chi-chi restaurant district around the corner. We hired a tour guide who spoke English very well. But that was pretty much it. Taxi drivers, cops, waiters and shop attendants generally had no English at all.

There is a fair amount of English translation of street names and other public signs. Tourist sites and museums often have English translation below the Chinese explanatory notes.

My brother, with whom I was travelling, speaks Cantonese but almost no Mandarin, the language where we went. He has a friend in Hong Kong with a gadget similar to the Babel Fish in Hitchhiker’s Guide the the Galaxy which you put in your ear and supposedly does simultaneous translation. But we missed a planned handoff so never tested the thing.

At our hotel in Hangzhou, the hotel clerks would speak Chinese into an app in their phone and then hold it out so we could read the translation. Then we’d reply in English and they’d read the Chinese translation. This worked reasonably well.

I learned on this trip that Google translate will allow you to capture text with the camera on your phone and will translate in real time—something I used to effect on menus and a clothes-washer in Japan. Did I mention that Google is banned in China?

Communication and Navigation

We were travelling with SIM cards in our phones acquired in Hong Kong but designed for travel elsewhere. As a result, our phones—and other devices tethered to them—could breach the Great Firewall.

So I could get essentials such as Wordle and the New York Times that are banned in China. I could also get Google and Google Translate. You may be thinking, then, that I must have been able to rely on Google Maps as well.

Well, yes, but not surprisingly, since it is banned, Google’s maps are not up to the standard you and I are accustomed to. Also, the English you are reading is only useful if it corresponds to the signage you can see. There are, of course, much superior Chinese mapping programs which, disappointingly, are all in Chinese.

One excellent way to get around in most urban places, and apparently some rural areas as well, is the Chinese equivalent of Uber, called DiDi. In order to summon a DiDi, though, you need to access it through a payment app such as WeChat Pay or the Alibaba equivalent (see next section).

The first time we took a DiDi, there was some confusion because the driver was insisting on some further information before we could depart for our destination. It turned out he needed the last four numbers of my brother’s Hong Kong phone number to verify the order. It took the intervention of a hotel doorman to sort it out.

When we left Shanghai, we took a long DiDi drive to the train station. When we arrived, people were running so fast and furious along the sidewalk to catch their trains that it was quite literally difficult to get out of the car. Travellers needed to pass their Chinese identity cards through a reader to get into the station, but we managed to get someone to look at our passports and let us in. The station was very crowded and hectic but we found our train (booked online in advance) without too much more difficulty.

Money

OK, so this is definitely a problem. China is very close to being a cashless society. I never saw a panhandler during our trip but my brother says that in parts of the country where there are some, they carry a QR code so they can take payment from an app.

Oh, and credit cards are also virtually unknown.

What that means is that you need to get either the WeChat Pay app or the Alibaba equivalent. WeChat is a bit like a combination of What’sApp and Apple Pay. To get on, I had to get an invitation from an existing member (my brother), and then I needed to apply separately for WeChat Pay. I had to upload a photo and a copy of my passport as well as give them my Canadian credit card. It took about a day to approve my application.

The app was a little confusing to me, because you can pay either by giving a merchant your QR code or by taking theirs. (It is generally their option, not yours.) Still, I was able to make a couple of purchases before I got stopped by a request from my Canadian bank (TD) to confirm that it was really me via a text to my Canadian number, which of course was not the one to which I had access on my phone.

Later that day I spent an hour on the phone with TD trying to sort this out. Eventually I was told—to simplify—that this was impossible, but that I should just keep trying and it would probably work. Which amazingly, it did.

Security

In my next post, I will tell you a little about all the surveillance I observed on this trip. But from a traveller’s perspective, safety and security is always an issue. I can truly say I don’t remember being in big cities elsewhere that seemed so safe. I wouldn’t worry if I left a cell phone or a backpack behind because I would be reasonably confident it would still be there when I returned.

Crowding

Outside of Shanghai, which attracts some Western businesspeople, we saw very few non-Chinese on this trip. In Hangzhou we were told that there had been Westerners coming for business and tourism prior to the pandemic, but this seemed to no longer be the case.

In addition, China is in a kind of recession (though not the kind we have in the West, where the economy actually shrinks).

You might think that all of this would mean that there would not be crowds in touristy areas. However, there remains a huge middle class in China and places like Hangzhou’s Westlake were teeming with people. There were long line ups for boats to popular sites and the pedestrian causeways sometimes slowed to a shuffle.

That said, as we got further afield, the crowds also dissipated.

Visa

Canadians currently need a visa to visit China, and obtaining one isn’t easy. The application is many pages long and demands all kinds of information about you, your past and current employment, places you’ve visited and so on. It also requires a detailed itinerary, including flight details, hotels and internal transportation plans. That was an issue for us because we wanted to retain some flexibility.

Once the form is filled, you need to go to a Chinese government office to be photographed and fingerprinted. There was also an issue with my itinerary because in two instances I was sharing a hotel room with my brother and those rooms were booked in his name. I was required to write out and sign several declarations that I was sharing his room, as ridiculous as that sounds.

I am lucky to live in Ottawa where there is the Chinese embassy, but if you don’t live in a city with a consulate, you may have to travel to one that does or use a broker.

Plan on several weeks for the whole process.

If you are thinking of going…

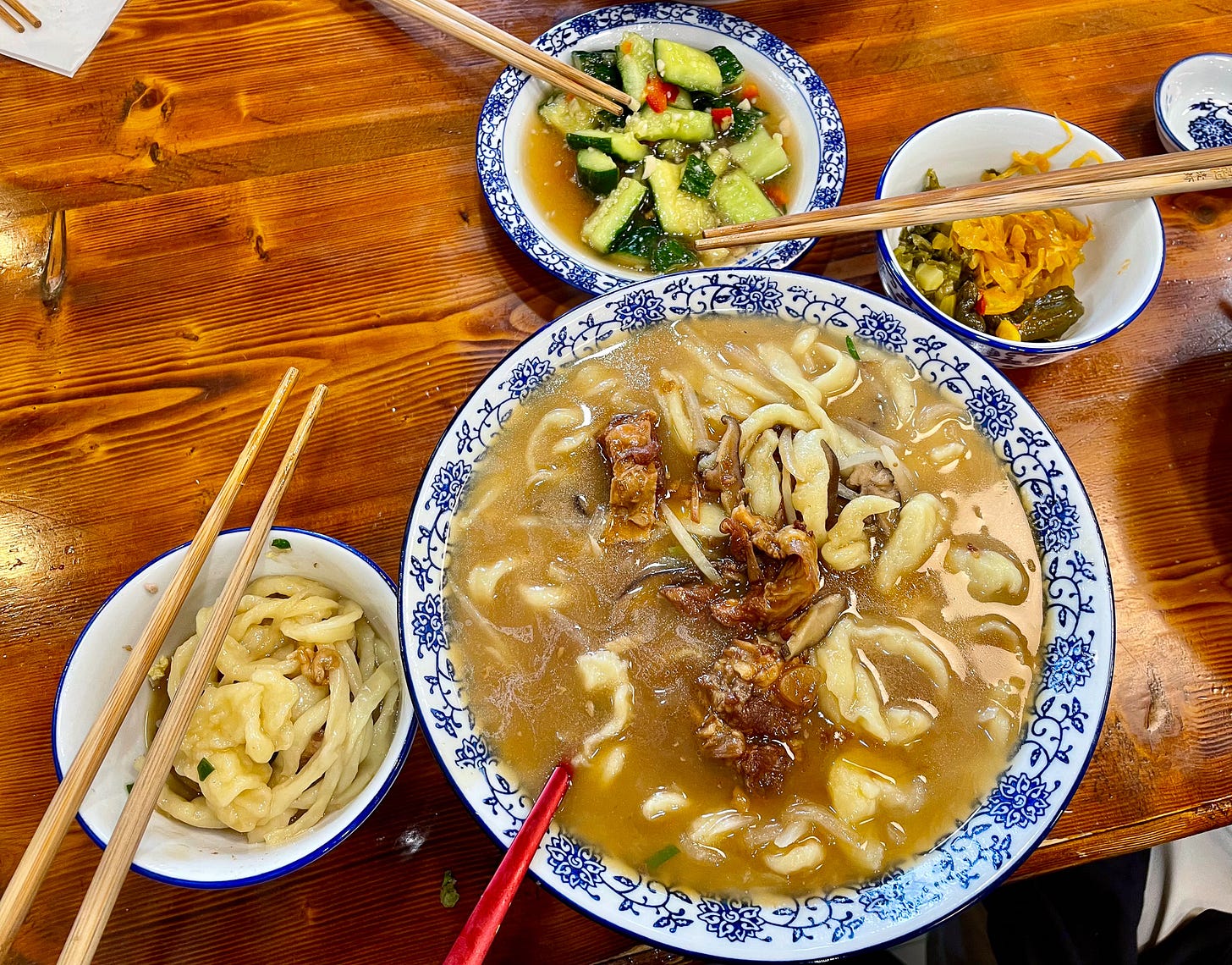

I found my visit to China fascinating, but the challenges are considerable. I was lucky to be with my brother who has travelled there a lot for business and tourism. And he had Chinese friends who accompanied us for several days, not only navigating the many challenges we would have faced on our own, but also steering us to some fabulous restaurants.

If you don’t have those kinds of supports, I would seriously consider some sort of guided trip.

Wow. Fascinating. Your piece makes me want to go to China, but creates much concern about the planning and preparation. Thanks for a good read.

Terrific info, Paul. Thanks much.