Denver

Indigenous art

When I headed down to the Denver Art Museum, I had no idea that the now-famous painting by Kent Monkman, The Scream, is housed there. Monkman, who is a member of Manitoba’s Fisher River Band Cree, has become well-known for using the tropes of Western art to subvert traditional Western narratives.

The Scream portrays Mounties, priests and nuns scooping up First Nations children to take them to residential school. It has drawn particular attention in Canada—even among those not otherwise interested in the visual arts—due to the recent explosion of attention in the news to the agony of the residential schools. But Monkman’s work has drawn international acclaim due to its focus on the recently-fashionable themes of colonialism and the history of Indigenous people in North America. He was commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to create two huge paintings for its Great Hall.

When I set out on this trip, I had no intention of posting repeatedly on Indigenous art, something that interests me but about which I know very little. I have been drawn along by the choices made by museum curators, whose own decisions reflect cultural trends in their milieu as well as in the general culture.

The Denver Art Museum had no fewer than four galleries dedicated to themes related to Indigenous people when I visited, two of them permanent collections and two special exhibits.

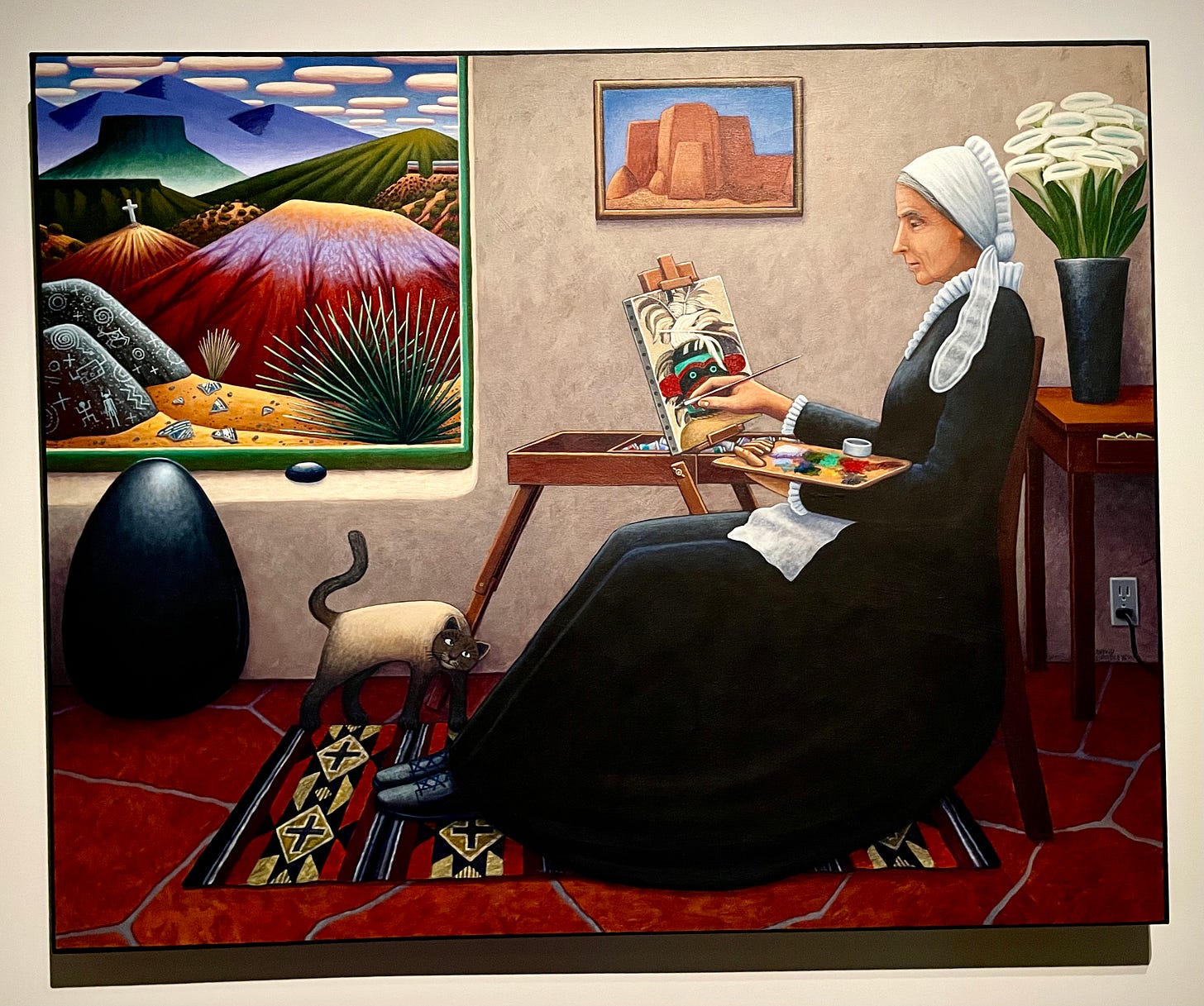

The permanent collection of contemporary Indigenous art includes mostly figurative works, many of them with an explicitly political or social dimension. In the painting below, the Chippewa artist, David P. Bradley, who objected to Georgia O’Keeffe’s severe modernist portrayal of the American Southwest, portrays her as Whistler’s mother.

Alongside the contemporary collection is a permanent exhibit of traditional West Coast art, including works from Alaska, British Columbia and the Pacific states.

The special exhibits included one on contemporary Indigenous photographers. A number of the photographs were send-ups of the portrayal of Indigenous people by whites.

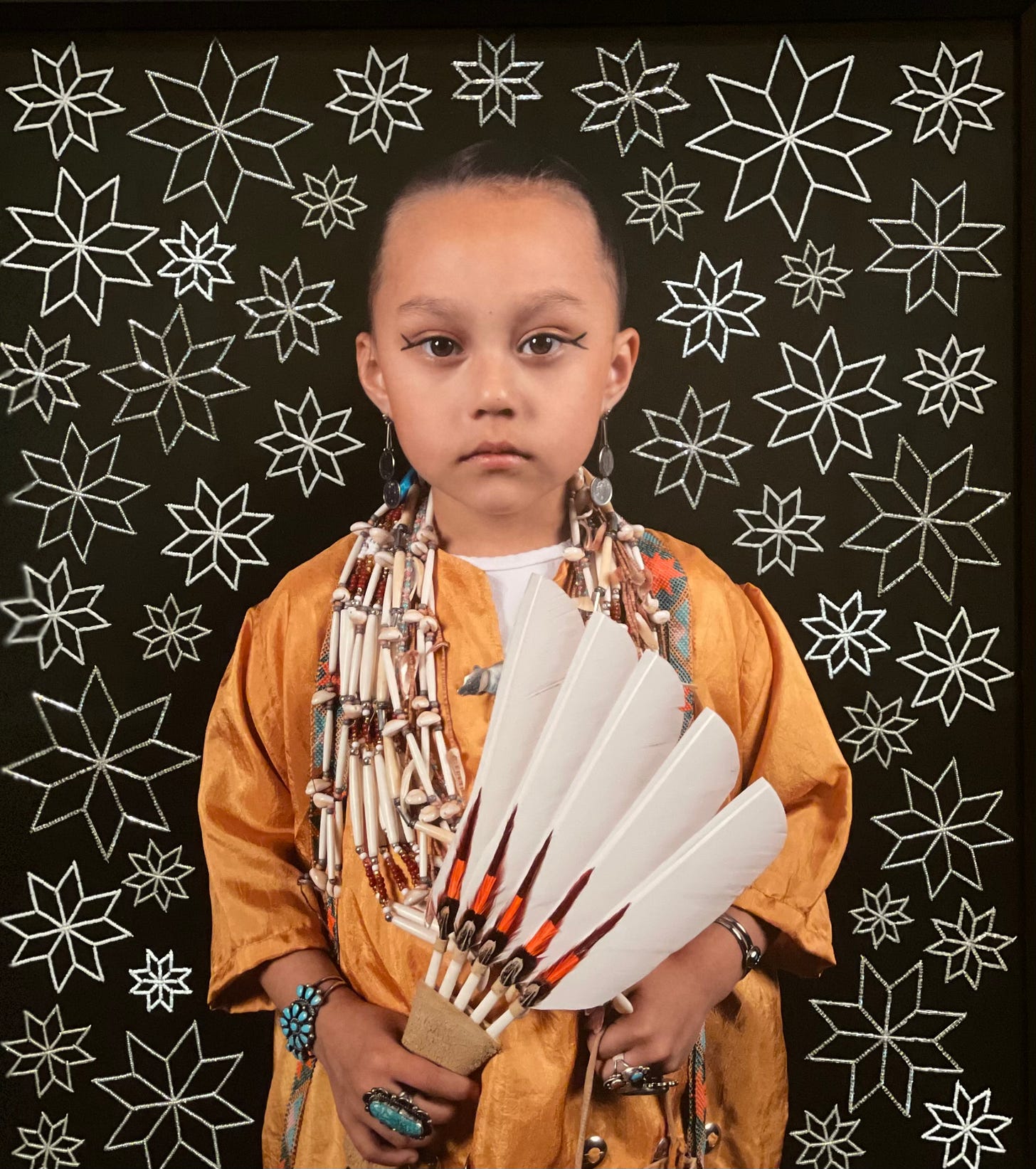

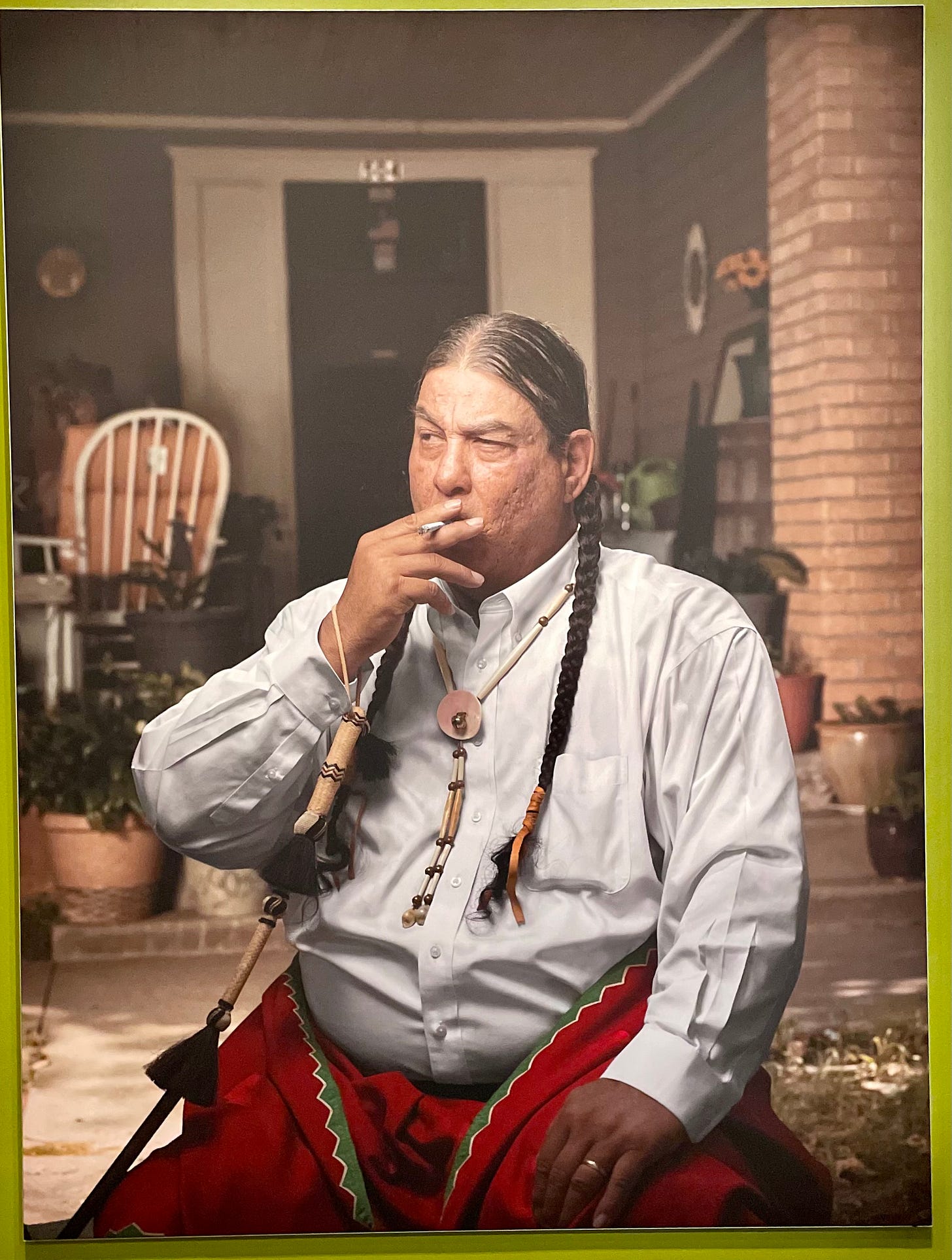

The exhibit also included some beautiful contemporary portraits of Indigenous people.

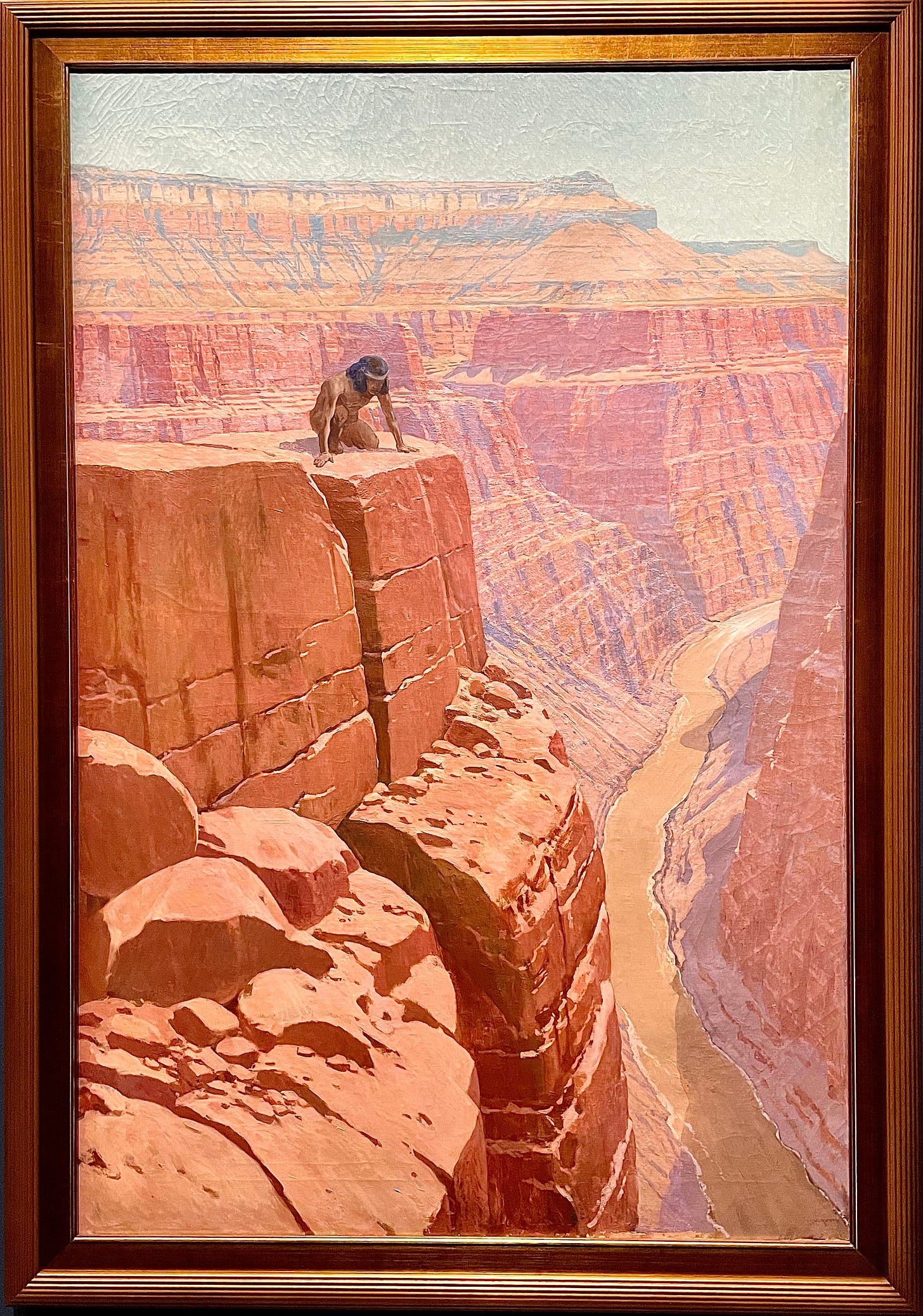

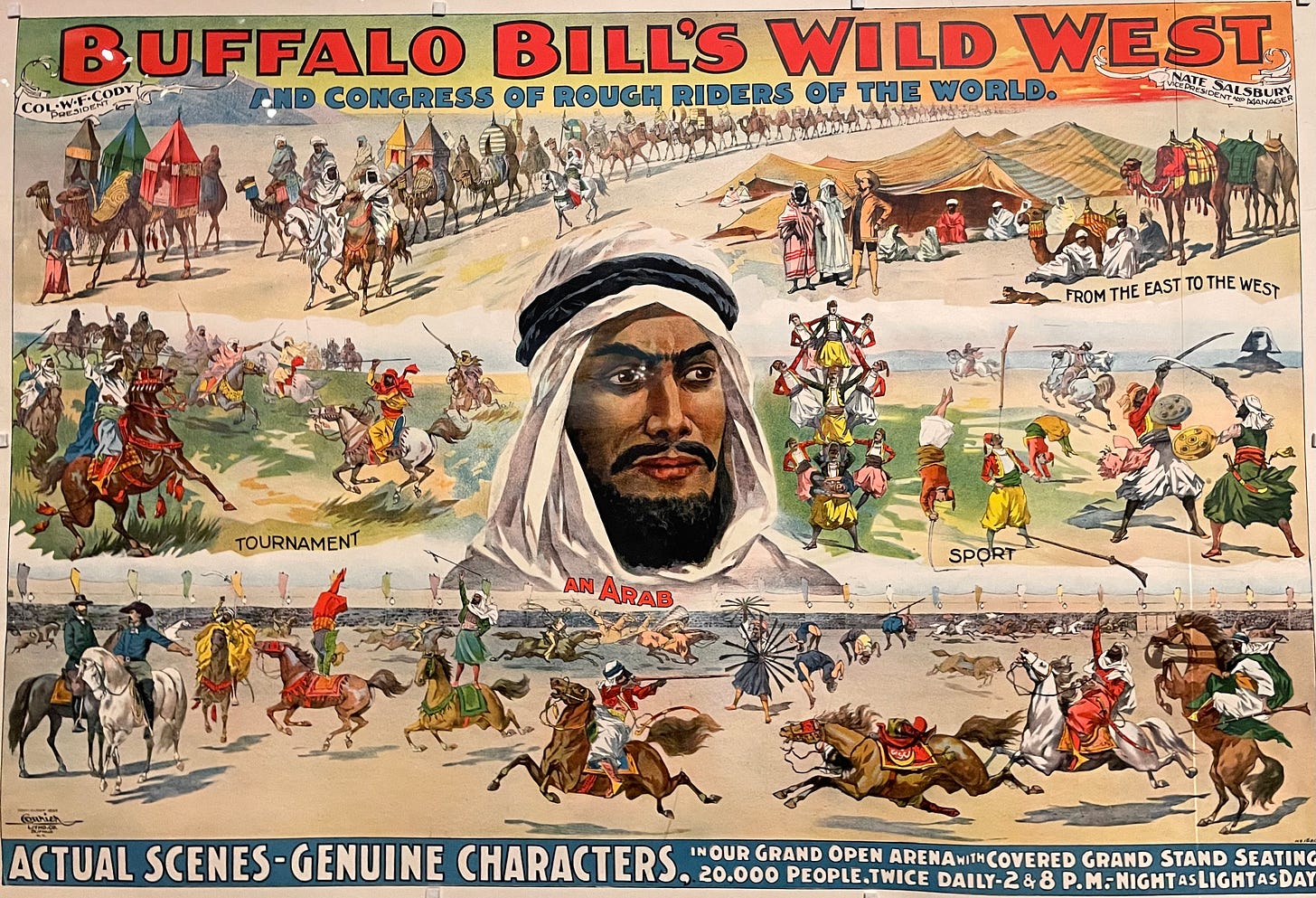

Another special exhibit, entitled Near East to Far West, features nineteenth century artistic portrayals of the American West by white Americans, arguing that they drew explicitly on on artistic themes and styles developed in the French artistic tradition of Orientalism.

Interestingly, just down the street, at the Colorado History Museum, there was an exhibit about the 1864 Sand Creek massacre in which U.S. troops slaughtered 230 men, women and children in Colorado. This is a second attempt by the museum. The first, in 2012, was entitled “Collision: The Sand Creek Massacre, 1860s-Today”, implying fault on both sides. It was shut down within weeks because of objections from the descendants of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people who died.

The current exhibit is called “The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal That Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever”. It is told from the perspective of Indigenous people, even to the extent that the interpretive panels use the first person plural “we”—invoking the voice not of curatorial authority, but of contemporary Cheyenne and Arapaho people.

Honestly Paul, without your posts, I would never have known about the Denver Art Museum and their indigenous collection. Well done. I'm a big fan of Kent Monkman and wish a painting like the one in Denver could be in the rotunda of the House of Commons. Luckily I saw many of his most provocative creations when the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia hosted his work, a few years ago.

Absolutely fascinating, Paul. Great work. Powerful art.