Mary Anning, Darwinism and the Jurassic Coast

An unsung (and not coincidentally female) hero of palaeontology finally gets her statue

I have been coming to Lyme Regis, a picturesque medieval market town in the west of Dorset on the English Channel, for about twenty years. My sister Marie and her husband bought a flat here back then. Like many people fleeing the hectic London life, they eventually bought a house and made this their year-round home.

Lyme Regis never changes much, but during my current visit here there was one noticeable addition on my stroll by the sea—a statue of Mary Anning.

The statue depicts Anning with a rock hammer in one hand, holding up an ammonite in the other. Ammonites are shelled cephalopods that died out around 66 million years ago and are among the most commonly found fossils around here.

The statue is pointed in the direction of a beach where, along with her brother, the 12-year-old Anning discovered the remains of an ichthyosaur, the first fully identified specimen of what we know today to be a prehistoric marine predator. Her find is now in an Oxford museum.

That discovery was among the first in an astonishing but tragically short career as a fossil-hunter which should have brought her great renown as a palaeontologist. But it did not, due to her humble background and the fact that she was a woman.

Stephen Jay Gould, one of the most eminent palaeontologists of the late twentieth century called Anning “probably the most important unsung (or inadequately sung) collecting force in the history of palaeontology.”

Nothing speaks quite so eloquently to her lack of recognition than the engraving on her tombstone when she died of breast cancer at the age of 47. She is almost an afterthought.

Anning was one of ten children, born in 1799. Her father was a cabinetmaker who supplemented his income by collecting small fossils and selling them to tourists. They were not yet known to be fossils. Rather they were “curiosities”, or “curios” for short.

Darwin did not publish his Origin of Species until 1859, twelve years after Anning died. So no one really knew what these curiosities were. Some thought that they were decorative ornaments planted by God for our enjoyment, or perhaps for His own glory. Others believed they might be vestiges from the Biblical flood.

Over her career, Anning’s discoveries included two nearly-intact plesiosaur skeletons as well as the first pterosaur skeleton found outside Germany. She identified the internal structures of cephalopods and correctly identified coprolites for what they were—fossilized poop.

The fossils she unearthed, and her understanding of them, drew the attention of some of the great scientists of her day—all men of course—including Louis Agassiz, the celebrated American geologist and palaeontologist. Lyme Regis was also popular among amateur collectors and scientists. If you have ever read John Fowles’ novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, set in the mid-nineteenth century, you may remember (ok, probably not) that the main male character, played by Jeremy Irons in the film version, came to Lyme Regis partly to collect fossils.

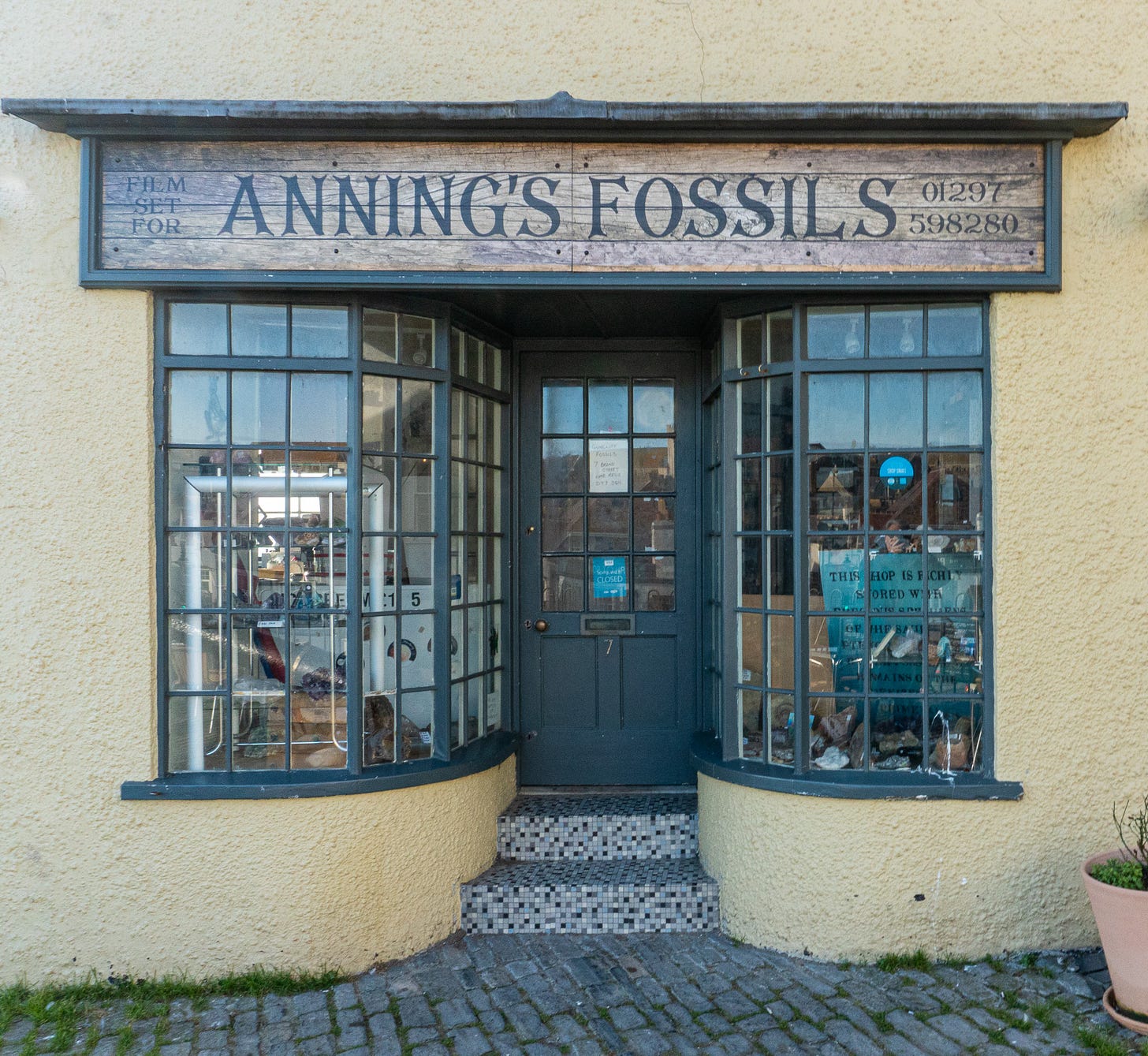

In an effort to stave off her family’s constant and precarious poverty, Anning managed to open a little shop servicing these visitors, and her customers included wealthy collectors such as the King of Saxony.

However, as a woman, Anning could not be a member of the prestigious Geographical Society of London, where many of her discoveries were presented. As a woman, she could not even attend their meetings. The scientists who depended on the fossils she unearthed, and often her insights into their biology and the strata in which they were found, frequently did not even mention her name when they wrote them up in the academic literature.

Not surprisingly this was the cause of some bitterness with Anning, who continued to struggle financially throughout her short life.

The reason there were—and are—fossils to find around Lyme Regis is an accident of geology, industry and weather. A combination of shale and limestone was laid down during the Jurassic Period, which occurred roughly 200 million to 145 million years ago, entombing the remains of ancient sea creatures.

At one time, the local hills were mined for the “lias” rock which was used for marine cement. This destabilized many of the cliffs that are subject to pounding winter sea storms, leading to frequent “mudslips”, spilling mud and rock onto the beaches below and revealing fossils in the muck.

This process of erosion continues today and low tide finds amateur fossil hunters combing the debris around recent slides. The local tourist board now promotes the region as the “Jurassic Coast”.

Plying the beaches underneath the eroding cliffs can be hazardous. One time my son Alex was walking ten metres back from the cliff when a small mudslide sent a glob of mud straight into his eye. More seriously, Anning’s dog, Tray, with which she is usually pictured, was buried and killed when he was out exploring with her one day.

Anning was a deeply religious woman, and and it isn’t known what she made of the contemporary explanations of the curiosities she found. One account, however, has her in a conversation with a minister who believed that God had created the world in a week. Anning is said to have pointed out that the different levels at which certain creatures were found suggested that they had lived at different times.

There is no doubt that once Darwin published his theory of evolution, Anning’s earlier discoveries provided powerful support. Indeed, it triggered an intensified interest in palaeontology in general, and the area around Lyme Regis in particular.

In recent years, the story of Mary Anning has been vigorously revived, no doubt because it speaks to modern sensitivities about the role of women. The movie Ammonite, released in 2022, stars Kate Winslet as Anning and the ubiquitous Soairse Ronan as her lesbian lover. It is a slow and sad movie which is not much favoured around Lyme Regis because of its entirely invented romantic plot.

More appreciated was a 2010 novel called Remarkable Creatures, by Tracy Chevalier (who is better known for Girl with a Pearl Earring). Chevalier’s book builds on Anning’s complicated real-life friendship and collaboration with another fossil collector, Elizabeth Philpot.

The idea for a statue came from an 11-year-old girl named Evie Swire. With support from her mother, as well as luminaries such as Chevalier and Sir David Attenborough, they raised more than £70,000 for the bronze statue by sculptor Denise Dutton. It is called “Mary Anning Rocks”.

Like any statue, it is designed to celebrate and flatter the values of those who erect it as much as the achievements of the person it honours. In this case, that seems like a good thing.

Great story. I’m glad to see an old injustice righted. There are echoes in this of Alfred Russel Wallace and his delayed recognition: a statue of him was erected only 10 years ago.

He did, of course, receive some recognition during his lifetime, but was mostly marginalized by Darwin and his ilk, who seem to have preferred their scientists to be male and of a certain social class. Unfortunate in his and Mary Anning’s cases.