Now is another winter of their discontent

Some thoughts on returning to a strike-bound Britain 45 years after the original Winter of Discontent--and why none of the troubles shake the mystique of the place for me

In August of 1978, I arrived in England on my way to Oxford for grad school. I cannot recall whether at the time I anticipated the explosion of industrial action that would occur in my first winter there. I do, however, remember the disruptions to everyday life as they happened: trains that did not run or did not run on time; shortages of staples such as sugar and bread; picket lines in front of hospitals; and most vividly of all the enormous piles of trash in London squares, with rats scurrying about, the result of a prolonged “dustmen’s” strike.

The media dubbed it the “Winter of Discontent” from a phrase in the opening line of Shakespeare’s Richard III, and it is remembered as the last in a series of crises that catapulted Margaret Thatcher into power in the spring of 1979.

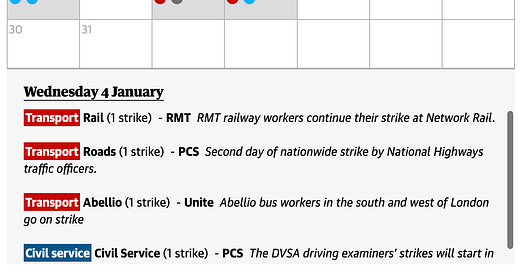

Now, the UK is once again in the midst of a wave of strikes and some of the media have revived the term Winter of Discontent. These days there are strikes of nurses and ambulance workers, midwives, bus drivers, physiotherapists, civil servants, teachers, and of course rail workers. The British media have taken to publishing handy little strike calendars, like the one below, from the Guardian.

I am going for a trip to England next month. It got me to thinking about the deep relationship I feel with the country, in many ways despite the particular path it has taken over these last decades.

The Britain I encountered in 1978 appeared very much like it might be in terminal decline. In the previous three decades or so, it had won a world war, but had been diminished from a great power to a middling one in the process. And it had lost an empire. The institutions that Labour had built in the aftermath of the war to reconstruct Britain, including the National Health Service and nationalized industries such as coal and steel, were precisely those in which the crisis seemed most acute.

The UK was also a considerably less prosperous place than Canada back then. In 1978, the UK’s per capita GDP was just under US$6,000, compared with Canada’s at just over US$9,000—so, roughly a third lower.

Oh, and then there were the bombings. One day my tube train inexplicably rocketed through Westminster Station without stopping when I was on my way to meet my sister, who worked on Fleet Street, then the home of the London media. When I emerged from the tube, the tabloids had already rushed out extra editions reporting that there had been a bomb on the parliamentary grounds. The Irish National Liberation Army had assassinated Airey Neave—who was then poised to become Margaret Thatcher’s Irish Secretary if she won the next election.

What I noticed most about England as a newcomer, naturally, was the conditions of everyday life. There was, by North American standards, no proper indoor heating. When I woke up in the morning I would stick my head out from under the covers and blow, assessing the temperature by the plume of vapour I emitted. The food was overcooked. The coffee was terrible. I used to joke that the plumbing had gone downhill in the 4th century when the Romans left and had not yet recovered.

Don’t get me wrong. I did not bellyache about all this at the time. Or at least not much. I found it part of the charm. In fact, at Oxford, I generally avoided other North Americans because they tended to spend so much of their time kvetching.

For me, there was a magic to living in England and it has only slowly dawned on me over my lifetime what that was. And it had to do with works of imagination. I grew up in Winnipeg. In those days, characters in novels never shopped at Eaton’s on Portage Avenue (or for that matter, in the Eaton’s catalogue). No one in the movies ever spent a summer hanging around Gimli or at Winnipeg Beach. Imagined people lived in unfamiliar places—at least unfamiliar to me.

England was utterly unlike that. I first visited England with my parents in my high school years. The very first day I was there, something remarkable happened—or at least this is how I remember it. At the time, I was reading a novel by Somerset Maugham, and in the novel a character turned off Piccadilly and walked down Half Moon Street, the single-block road on which our hotel, the Flemings, was located. It was a revelation to me that people in novels lived in real places, or rather in places that were simultaneously real and imagined. As I was writing this piece, I looked Half Moon Street up on Wikipedia and discovered that not only did Maugham live there for a time, but so did James Boswell, Siegfried Sassoon and Sax Rohmer. And Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest is set there too.

Of course, living and studying in Oxford, it was impossible to shake the feeling that you lived in a literary landscape. Trading in the cinder brick and acoustic tile of the University of Manitoba for the magnificence of Oxford’s libraries, lecture halls and seminar rooms seemed surreal—it made me feel slightly giddy. It was the sensation of a young man from the fringes of empire coming to its heart.

Even when you joined your “mates” for a “few pints”—that staple of collegiate life—you might find yourself drinking at the Eagle and Child, where Tolkien and C.S. Lewis used to share their early drafts with a little club called the Inklings. Or you could go across the street to the larger Lamb and Flag, where Thomas Hardy is said to have written Jude the Obscure.

While I was a student at Oxford, probably the two biggest British TV serials of the time were Brideshead Revisited, based on Evelyn Waugh’s novel, and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, based on John le Carré’s. Every day I walked or cycled by places portrayed in Brideshead and I normally studied in a library building called the Radcliffe Camera which figured in the opening sequence of Tinker, Tailor.

In those years, I also spent a lot of time in London, often researching in the British Library, then still housed in the famous reading room in which Marx had researched Das Kapital, under the dome of the British Museum. (It is now a lovely restaurant!) London’s famous West End theatre district was walking distance away. The West End had fallen on hard times amidst the general gloom, but the result for me was that as a student, I could get a last-minute ticket for a single pound to sit up in “the gods” as the upper deck was called, from which you could sneak down at intermission to one of the many empty seats. Later, my sister Marie became the theatre critic for LBC radio, and so I could sit with her on occasion, quite legitimately, sixth-row centre.

In London, I loved the bustle at rush hour of that magnificent architectural tribute to the wealth of 19th century Britain, Waterloo Station, where I could look up at the big board and catch a train in seven minutes to where Marie lived in Wimbledon, or, if I ran, catch one leaving in two.

But of course, for the British, these romantic feeling of mine could not have been more foreign as they lived through the Winter of Discontent. The prime minister of the day, Labour’s Jim Callaghan, seemed a little lost amidst the multiple crises. So far as the strikes were concerned, he tried a kind of shuttle diplomacy between employers and the unions (with whom his party was closely connected). But the talks produced nothing and there was a prevailing view, certainly in the Tory press, that the government was complacent.

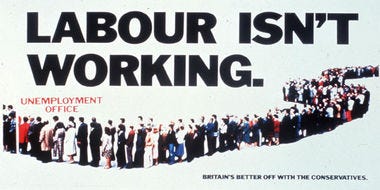

I am not sure if it is still the case, but in those days Commonwealth citizens like me living in the U.K. could vote. I cast my ballot for Labour without much enthusiasm in the election held in May of 1979. Thatcher’s Conservatives won a solid victory after a campaign run in part on a brilliant slogan devised by the advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi.

Ironically—or perhaps inevitably—the unemployment rate under Mrs. Thatcher (as she was universally known back then) did not fall, but rose spectacularly.

I remember that when UB40 released One in Ten, their hit song about unemployment, in 1981, the math was not precisely right. Unemployment was higher that. It peaked under the Thatcher government at around 13%.

I am the one in ten

A number on a list

I am the one in ten

Even though I don't exist

Nobody Knows me

Even though I'm always there

A statistic, a reminder

Of a world that doesn't care It is not for me here to assess the wisdom of Thatcher’s policies—they seemed unnecessarily cruel at times—or of those of Tony Blair, which were in some ways a kinder, gentler extension of hers. But there’s no doubt that the original Winter of Discontent was an inflection point of sorts. By 2021, the the UK’s GDP/per capita was US$47,000, compared with US$52,000 for Canada. In other words, today’s Brits are not only much better off that they were back when I first arrived; they are a lot closer to the level of prosperity we enjoy as Canadians, which of course is also much higher than it was nearly half a century ago.

Part of what happened in between was that the UK substantially de-industrialized and greatly financialized. In 1952, there were more than 700,000 coal miners in Britain. Today there are about a thousand.

Meanwhile, “The City”, as London’s financial district is known, has been one of the great engines of globalization, second only to Wall Street. When I am in London next week, I will be staying with friends in their apartment near Canary Wharf. As a student, I had an occasion to retrieve a trunk from a dockside warehouse in that East End neighbourhood: it was decrepit and frightening. But even while I was still living in the UK, Canada’s Reichmann brothers began developing the area. Today, it is utterly transformed. Wikipedia describes it as “one of the main financial centres in the United Kingdom and the world.”

Of course, the UK has also famously become a much less equal society in that same time. Here is a chart of the Gini coefficient, one measure of inequality, from around the time I was there to the present day.

Interestingly, the UK was a much more equal society than Canada when I arrived there as a student. Today, the two countries are about the same.

My sister and her husband, Gordon, like many of the post-war generation in Britain, were lucky to ride an enormous upswing in property values, particularly in the London area, in the years after I left. Gordon also benefitted from Thatcher’s policy of selling off “council housing”—in which most of the British lived at the time—to the tenants, enabling them to cash in on the boom.

Today Marie and Gordon live in the charming Dorset seaside town of Lyme Regis, incidentally the setting for Jane Austin’s Persuasion, and the home of the novelist John Fowles. The picture below is one I took of Lyme’s famous Cobb—a sinuous breakwater a few minutes’ walk from my sister’s home. Off in the distance is the famous hill from the British TV detective drama Broadchurch. And for those of a certain age, the tip of the Cobb is also the place from which a hooded Meryl Streep gave her mysterious backward glance at Jeremy Irons in the midst of a storm in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, based on Fowles’ novel.

The burst of economic growth the UK enjoyed in the decades immediately after I left did not sustain itself deep into the 21st century. David Cameron’s Conservative government, elected in 2010, pursued an unusually stringent form of austerity by international standards in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. And Brexit, of course, has led to deep stagnation—a spectacular case of national self-harm.

Meanwhile, the UK has been living through an elongated constitutional crisis, the kind of thing Canadians are familiar with. Under Tony Blair, Scotland and Wales were granted their own parliaments, a bit like our provincial governments, and the Northern Irish legislature at Stormont was restored. One way of looking at this is that it was yet another stage in the dismantlement of the British Empire: after all, Ireland, Wales and Scotland were in some senses the first colonies.

Not enough thought was given at the time to where this left England, which did not get its own legislature, but continued to be ruled from the national parliament at Westminster. The UK had, of course, belatedly joined Europe in the 1970’s, in an attempt to find a post-imperial place in the world. One way of looking at Brexit is as a specifically English (rather than British) assertion of local nationalism as the last vestiges of empire peel away.

People argue about whether one of the UK’s recent prime ministers—all Tories— was the worst in British history. They are all candidates: David Cameron, who held a referendum on Brexit, which he opposed, and lost; Theresa May, who tried to reach a form of Brexit that Europe and her party could agree on, and failed; Boris Johnson, who achieved Brexit only by, in effect, creating a trade border down the Irish Sea which is completely unworkable; and Liz Truss, who, well, was Liz Truss.

But whichever you choose as the worst, let me state as a semi-expert in this area—I studied British political history at Oxford—never before in the country’s history has it had a similar run of four colossal failures as prime ministers all in a row.

This Winter of Discontent, luckily, started off relatively mild. Luckily because during 2022 electricity prices rose 64% and natural gas 129%—even after government subsidies. But the weather has more recently chilled. Earlier this week, a company called Octopus paid British consumers that belong to its scheme to turn off their kettles and their washing machines to avoid a potential blackout over dinner hour.

My sister, whom I will be visiting on this trip, tells me she is keeping her house at 19 degrees—pretty cool by Canadian standards. But it’s worth noting that when I was a student over there, a house like hers probably would not have had central heating at all.

On my very first visit to the UK, I remember a eerie feeling of familiarity even as I saw things for the very first time. I recognized the forests from the Narnia books. The factories made me think of Dickens.

And nowadays, the years I spent in England as a student are themselves becoming part of the cultural landscape—in The Crown, for instance, and even more interestingly Sherwood, a whodunnit wrapped around the enduring enmities in a village wracked by the miners’ strikes in the Thatcher era.

I’ll never shake that sense when I am over there that I am in a place of someone else’s imagination as well as of my own prosaic reality—and that of the people who actually live there.

Love London for many of the same reasons, despite the decline. But how are you travelling east to London at same time as you are travelling west in your EV?

The profits went to London, Manchester, Brighton etc to keep business taxes low while encouraging foreign investment in England. My family in Glasgow saw few benefits. I have cousins now in their 60s who have never worked! Living on the dole, drinking in the pubs, watching Rangers on TV. The ship building industry on the Clyde collapsed, unemployment soared, and young educated parents (like mine) emigrated to Canada, Oz, NZ. No wonder the SNP took root in the 70s.