I wouldn’t call myself a particular enthusiast for modern art. In fact, I think I may be drawn to photography partly because I enjoy its emphasis on the representational that the fine arts have turned away from in the last century and a half.

In recent years, however, on my frequent visits to London, I find myself drawn repeatedly to the Tate Modern, located on the South Bank of the Thames, across the Millennium Bridge from St. Paul’s Cathedral, in a renovated power station.

The most striking feature of the Tate Modern is the enormous Turbine Hall which allows the exhibition of works mounted on a truly stunning scale. I confess that it is that pure scale—and the scale of the ambition—of some of these works that I find so memorable.

Behind the Red Moon, by the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, is currently on display, and consists of three gigantic textiles. From a distance, you can see shapes that hint at human and animal bodies or celestial objects.

I confess that I would not have recognized that the collection of works was intended to say something about Europe and Africa and their commodity culture based on colonial trade routes, as the curation notes inform us.

However, I was impressed by the cascade of colours and was amazed to discover that these monumental works are created by stitching together with copper wire tiny discarded bits of beer bottles and cans recycled in Nigeria. It confounds me that anyone would ever embark on a project this time-consuming and laborious. If an idea like that ever occurred to me—which it would not—the next thought I would have would be “but what if it’s shite?” and that would be the end of that.

But on this trip to the Tate Modern, what interested me most was a special exhibit called Capturing the Moment which explored the relationship between photography and painting. Anyone with a serious interest in the history of photography knows well how the conventions of 19th century landscape and portrait painting shaped photography as it emerged at that time.

What I had never thought much about was the way in which photography thudded into the side of the visual arts, especially painting, stealing away some of its force to represent the world around us in a literal way.

The curators of this exhibit argue in effect that photography forced artists—or perhaps liberated them—to find something else to do rather than capturing a moment in a literal way, something photography does so well. Thus, Picasso’s cubism, collapsing perspectives or even time.

Some of the power of these paintings derives from the implied contrast between what the artist is showing us and what we think we might have seen had we been there at the moment—or if someone had taken a snap.

Although the exhibit was dominated by painting, there were a number of photographs that illustrated the way in which painting influenced photography which in turn influenced painting and so on.

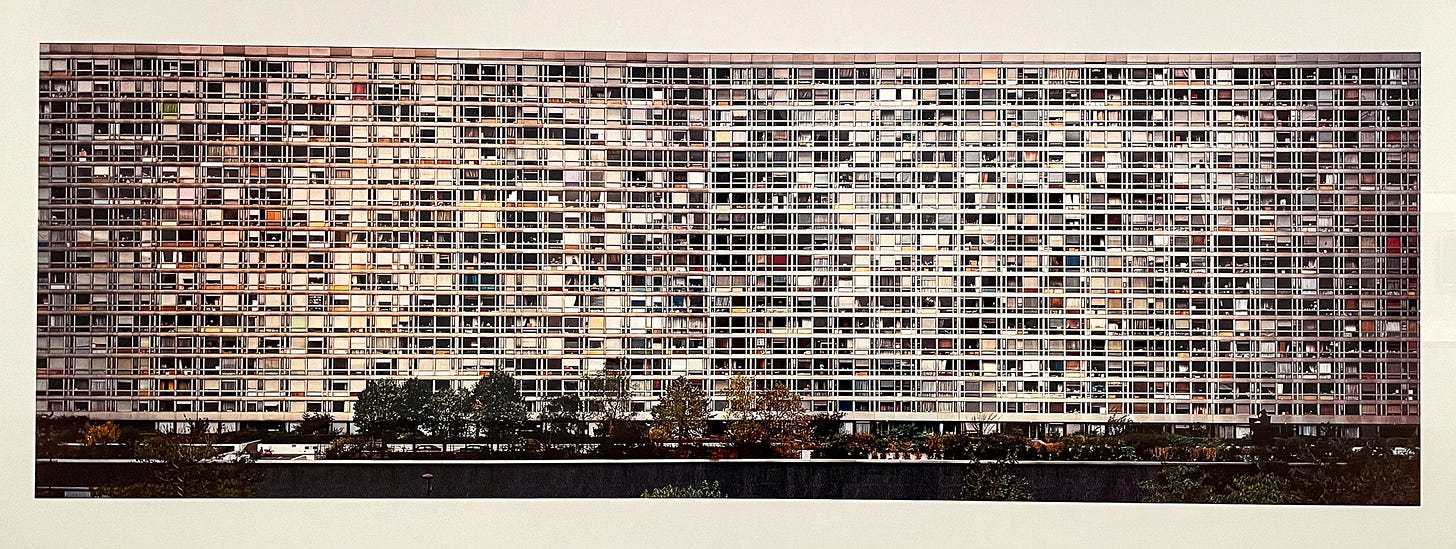

When you look at the photograph immediately below, which portrays a French housing development, it is hard not to be reminded of abstract artists such as Piet Mondrian.

One of the last paintings in the show is David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) which was based on a series of photographs. Of course, when I stopped to think about it, we all take it for granted that some modern artists use photographs as part of their process as much as they do artist’s sketchbooks. And process inevitably affects product.

There’s a piece this week in the Times on Cindy Sherman, for those of you who appreciate photography as art.

Great piece, as always. You may enjoy the X account ArtButMakeOt Sport. It also explores the interface/relationship between painting and photography.