On my first visit to England, when I was about 15, I remember feeling a mixture of strangeness and familiarity. The strangeness was easy enough to explain: it was my first time out of North America. But it took me a while to recognize what made it feel familiar. It was reading.

When I was in about grade four, I discovered the Narnia books, which I read and re-read. By the time of that first visit, I had graduated to George Orwell and Graham Greene. The flora, the fauna, the drizzle, the curvy shape of the hedgerows, not to mention the double-decker buses, Big Ben and Trafalgar Square were the backdrop to the lives of people who existed in books.

Growing up in Winnipeg, it was a revelation that the characters who populated books lived in real places. Even Canadian authors wrote about cities I barely knew, like Montreal and Toronto. Perhaps you are thinking that Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel was on every high school curriculum back in my day. Not at my Catholic boys’ school. We studied Robertson Davies. And besides, Neepawa isn’t Winnipeg.

I remember the first time a character in a book I was reading appeared in familiar terrain. For a while in my early teens, I was into dystopian novels such as 1984 and Brave New World. I picked up Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 book It Can’t Happen Here, which is eerily resonant today: it details the rise to power of a fascist dictator in the United States. In the novel, one rebel leader escapes to Canada and (if half-century old memory serves) has breakfast at the Fort Garry Hotel with the mayor of Winnipeg.

In my childhood, the Fort Garry remained an opulent ornament to the city; my grandfather occasionally treated us to dinner there. I remember wanting to jump up and tell someone when I read that passage but also feeling faintly ridiculous since the reference was literally a single sentence.

That deep sense that books happened elsewhere set in firmly with me before I had reached the age of twenty and I have never shaken it. Even a heroic inhalation of Carol Shields and Miriam Toews wouldn’t turn Winnipeg into a literary landscape for me now.

These days, I spend at least a few weeks a year in Lyme Regis, on England’s Dorset coast, where my sister lives. Dorset may sit most squarely in the literary imagination as the heart of Thomas Hardy’s “Wessex”: Tess of the d’Urbervilles and The Mayor of Casterbridge are some of his many books situated in this part of England. Casterbridge is a thinly disguised Dorchester which was Hardy’s hometown and remains the administrative hub of the county.

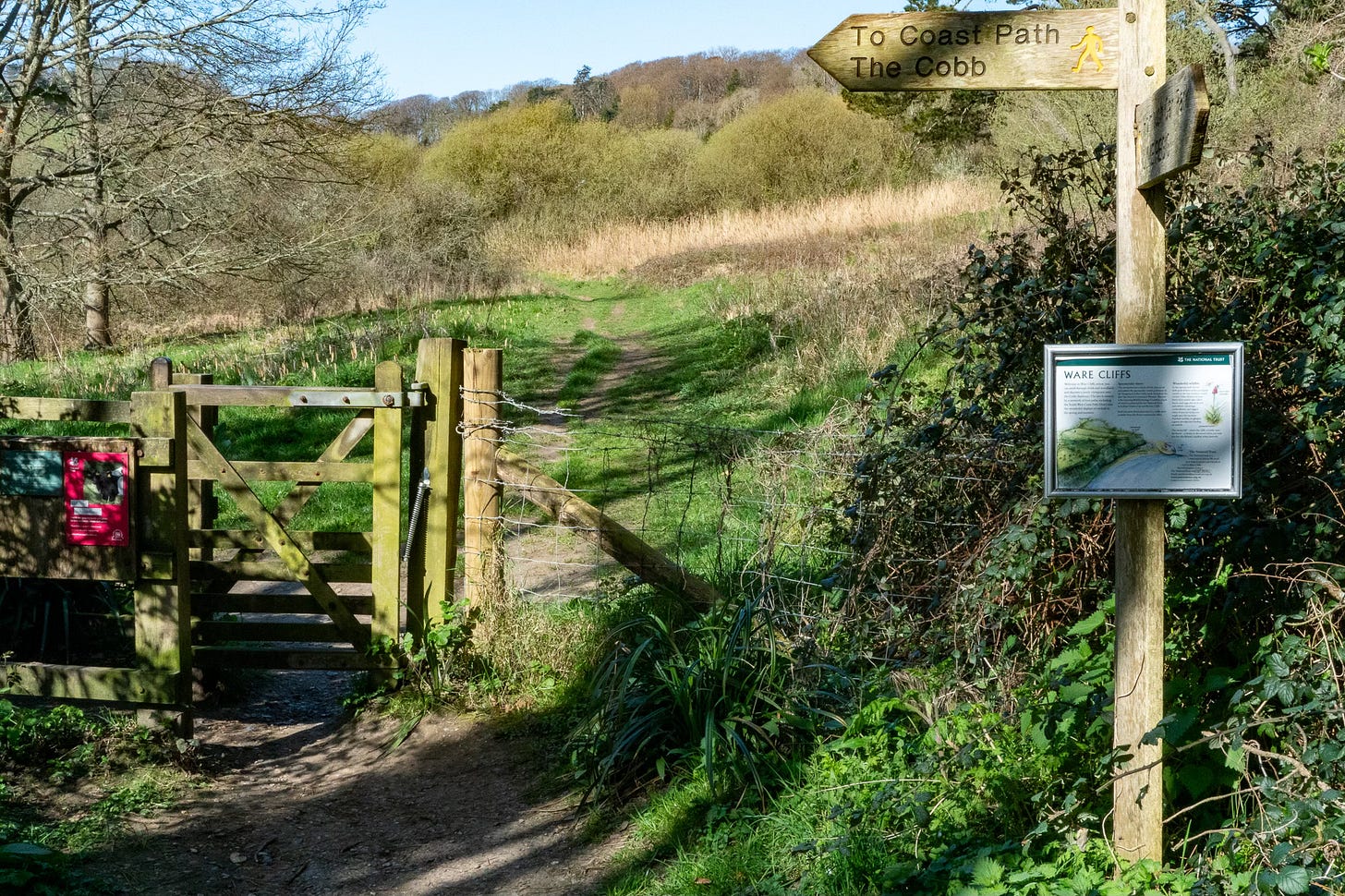

But Lyme Regis is also the setting of several fine novels. In Jane Austen’s Persuasion, one of the characters stumbles off Lyme Regis’s most famous landmark, The Cobb, and has a concussion. (I posted about the Cobb when I was here last year.)

As I flew over to England last week, I read Tracy Chevalier’s book Remarkable Creatures, which is set in Lyme Regis. Chevalier is better known for Girl with a Pearl Earring. I wouldn’t rank Remarkable Creatures among the best books I have ever read, but part of the enjoyment was watching in my mind’s eye as characters passed along familiar streets and then, when the tide was low, out along seaside beaches and cliffs I know well.

The novel’s protagonist is Mary Anning, a historic figure I’ve written about before. Anning was a poor and poorly educated woman who lived in the early nineteenth century and who had a genius for discovering fossils. She dug up the skeleton of an ichthyosaur and two plesiosaurs—extinct prehistoric animals whose significance was not fully understood in those years before Darwin.

Not much is known about Anning’s interior life, except that she was deeply religious and somewhat troubled about how her discoveries meshed with conventional Christian accounts of creation. But modern artists like Chevalier usually extract a feminist theme from her life because while renowned (male) scholars built their careers around her discoveries, her immense contributions to science went largely unacknowledged in her time.

The most famous novel set in Lyme Regis is undoubtedly The French Lieutenant’s Woman, written by John Fowles who lived much of his life here. There are echoes of Hardy’s Tess in both subject and style, though Fowles’s book is also thoroughly modern in tone. Set in the mid-nineteenth century, the novel begins on the Cobb where a gentleman on holiday strolling with his fiancee sees a forlorn-looking woman at the end of the breakwater in apparent danger from a storm.

If you know the story only from the successful movie (scripted by Harold Pinter) in which Meryl Streep plays the mysterious Sarah Woodruff—the French lieutenant’s woman of the title—you may remember mostly the love story. But the novel is also a meditation on the tension between scientific modes of thought gaining currency in the Darwinian age and older traditions that elevated nature, intuition and faith.

Charles, the male protagonist, is in Lyme mainly because his fiancee has been sent there for her health, but he represents a generation of gentleman scholars drawn to Lyme in the light of Anning’s discoveries by the fossils perpetually yielded up by the regions’s crumbling cliffs.

Though the story begins on the Cobb, some of its most powerful scenes play out in the Undercliff, a spookily shady forested area west of town created by cliff falls.

In the opposite direction, a few dozen kilometres east along the coast is another strange geological formation called Chesil Beach, a nearly 30-kilometre long berm of pebbles (called shingle) seemingly carefully graded for size by the pounding of the waves. The beach encloses an equally long tidal lagoon called the Fleet.

This is the setting for Ian McEwan’s novel On Chesil Beach, which takes place in the 1960s. A honeymooning couple at a seaside hotel have a fumbling first sexual encounter which deeply divides them despite their intense love for one another, leading to an annulment of their marriage. Years later, the erstwhile groom looks back on their experience and regrets the life they might have led had he been more accommodating to his young wife’s struggle with intimacy.

It is a profoundly sad account of misunderstanding in the midst of love—an exploration of regret. It had a humorous coda, though. In a radio interview about the book, which was short-listed for the Booker Prize, McEwan mentioned that he had scooped up a few pebbles from the beach and kept them on his desk while he wrote. It turns out that every one of the billions of pebbles on the enormous beach is precious. Conservationists were outraged and the local council menaced him with a £2000 fine.

"I was not aware of having committed a crime," McEwan said. "Chesil Beach is beautiful and I'm delighted to return the shingle to it."

A very enjoyable ramble through some fondly remembered books, Paul.

Thoughtful reflections. Wonderful pics. Especially the one of the Cobb and its shadow.