Many years ago, I started posting a list of my favourite books from the previous year on Facebook around New Year’s Day. A few people urged me to move the post up because they liked to have it for gift ideas, which I did. And then more recently, I moved it here to Substack.

So here it is for 2024.

My tops in fiction first.

James, by Percival Everett. This novel is a retelling of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, this time from the perspective not of Huck Finn but his runaway slave friend known as Jim in the original novel. This book is both a homage and a corrective to Twain’s. As a lover of the Twain original, I found it took me awhile to adjust to Jim/James’ very different voice. But once I did, I found this retelling moving and revealing.

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, by James McBride. There is a murder mystery at the heart of this novel, set in Chicken Hill, a rundown neighbourhood in industrial Pennsylvania in the inter-war years. The Black and Jewish residents each face racism but in different ways that drive them both together and apart. But the story is not about groups but vividly realized individuals, struggling to make their way and be true to who they are in the face of corrosive social forces. I don’t think McBride’s books ever make an errant step.

Small Things Like These, by Claire Keenan. This exquisite little book tells the story of an ordinary man in an Irish village who discovers in himself an unsuspected courage when he realizes what is happening to unwed mothers housed in a local convent. Both troubling and inspiring. The movie version with Cillian Murphy is about to hit the screens, but this is such a short novel—really a novella—that you might want to consider reading the book first. You can do it in a sitting or two.

Just a Mother, by Roy Jacobsen. This is Jacobsen’s fourth book in the Barroy Chronicles. The Second World War continues to haunt Ingrid and those in her remote corner of maritime Norway. If you haven’t read the earlier books start with the The Unseen. Jacobsen is my favourite novelist these days. His ability to build story and character from granular description of the daily lives of people living at the edge of subsistence is remarkable. If you haven’t heard of him, check out this profile in the Globe and Mail a couple of years ago. They call him the best novelist you may never have heard of.

On Java Road, by Lawrence Osborne. My brother suggested this book to me while I was visiting Hong Kong last spring. It is a mystery set amidst the political turmoil of a few years back with a washed-out British ex-pat journalist as its narrator. I found it an interesting way into this weirdly complicated society at a precarious time.

Honourable Mention: The Slow Horses series, by Mick Herron. Like many people, I was alerted to these books by the wonderful TV series starring Gary Oldman. Herron is not the new LeCarré, as the blurb would like you to think. His skills and ambitions are more modest: to entertain, which he definitely does. The first few books are mirrored by the early seasons of the TV series, so they cover familiar ground, but I found myself as engaged and amused as I did when I watched them.

And here is the non-fiction.

American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. This is the 2006 book that provided the spine of the movie Oppenheimer. I remember intending to read it when it came out but never did until after seeing the movie, which I enjoyed but thought never fully wrestled with the contradictions in the character and actions of this complicated genius. This is a brick of a book (784 pages) but written with great verve. In the end Oppenheimer remains something of an enigma, but a fascinating one.

The Wide Wide Sea, by Hampton Sides. I probably have too many salt-stained epics on my lists, but I thought this account of Captain Cook’s final and fatal journey to the other side of the earth was unique in many respects. The author spins a fascinating yarn, but he is also sensitive to modern concerns over imperialism and tries to understand how Cook was seen by the people he encountered without losing sight of how he saw himself.

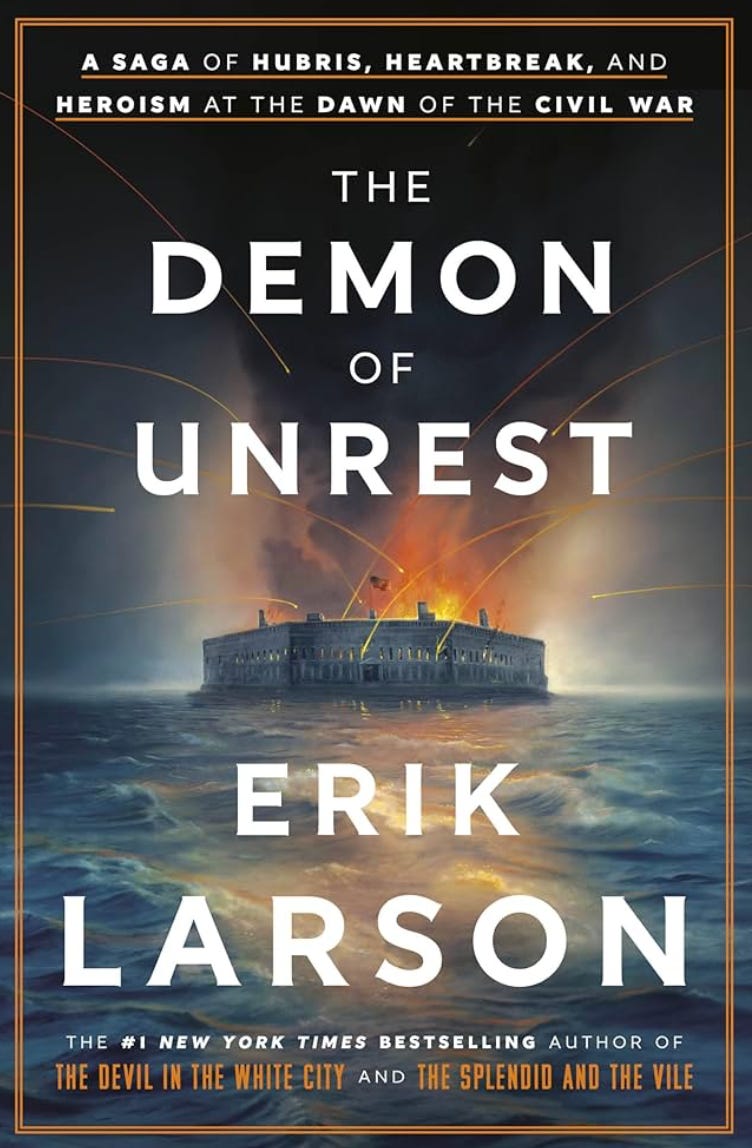

The Demon of Unrest, by Erik Larson. I don’t think there’s another writer of creative non-fiction who so successfully dives into familiar topics and manages to excavate new stories and perspectives. This book is a kind of micro-history of the Civil War, centred on Fort Sumter, the island fortress off Charleston, South Carolina where the war began when the South attacked. A completely fresh take which will interest people whether they’ve read a lot about the war or this is their first foray.

Silk Roads, A New History of the World, by Peter Frankopan. This is a bit of a cheat because I am only halfway through it. But I know it should make my list. The subtitle is a bit grandiose, but the author’s aim is to shift us away from a Eurocentric vision of the world, spreading out from the Mediterranean as it were, to an approach that centres the lands between East and West—the places that warriors, traders, missionaries, scoundrels and saints traversed as civilizations became connected enough to become a single world. A scholarly book written for the layman with great zest.

And now a pair of non-fiction books, one very sobering and one more hopeful about our neighbours to the south.

The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory, by Tim Alberta. This sobering book chronicles the takeover of the American evangelical church by the cult of Trump. Alberta is himself a conservative Christian whose father was a pastor. (His day job is as a writer for the Atlantic.) His deep roots in the church allow him an unparalleled access and afford him an incomparable level of insight, suffused with sadness and disillusionment.

A Fever in the Heartland, by Timothy Egan. Did you know that sports teams at Notre Dame University were officially dubbed the “Fighting Irish” after a group of its students clashed with a mob of anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s? This book tells the story the Klan’s political takeover of Indiana in the 1920s and the backlash that brought the organization down in the state and precipitated its national decline. The author prefers a good story to nuanced historical precision, but unless you are a deep student of the local history, I am guessing you won’t be bothered.

Finally, a misfire: The Message, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. I am a great admirer of Coates’ writing, which at its best combines deep reporting with brilliant prose. I fully expected this book would make my list even before I picked it up. But it read to me like it was written to satisfy a publisher’s demand for something—anything. It is framed as a set of essays for his writing students, one from Senegal, one from a town in South Carolina where they are trying to ban one of his previous books, and one from the West Bank. But they are weirdly superficial. In Senegal he ruminates on slavery but talks to almost no one. In South Carolina, he goes to a school board meeting about his book, but one attended mostly by his supporters—and that’s it. In the West Bank, which he visits for just two weeks, he is struck by the parallels with Jim Crow—fair enough—but is much more concerned with the moral clarity this insight brings than the political complexity of addressing the region’s agonies. I’d give it a miss even if you are an admirer of his other work—maybe especially if you are.

Thank you Paul. I loved two of Roy Jacobsen's novels thanks to one of your previous lists. See I have some catching up to do. I have an unfortunately high pile (4 actually) of to-read books and must get myself a kindle or neighbours will start mistaking me for a hoarder.

Thank you Paul! I appreciate your thoughtful comments. I’ve added the non-fiction ones to my reading list.